Why should anyone boot *you* up?

This post had some discussions on Hacker News, see the thread.

Imagine the following scenario:

- We develop brain-scan technology today which can take a perfect snapshot of anyone’s brain, down to the atomic level. You undergo this procedure after you die and your brain scan is kept in some fault-tolerant storage, along the lines of GitHub Arctic Code Vault.

- But sufficiently cheap real-time brain emulation technology takes considerably longer to develop—say 1000 years in the future.

- 1000 years pass. Everyone that ever knew, loved or cared about you die.

Here is the crucial question:

Given that running a brain scan still costs money in 1000 years, why should anyone bring *you* back from the dead? Why should anyone boot *you* up?

Compute doesn’t grow in trees. It might become very efficient, but it will never have zero cost, under physical laws.

In the 31st century, the economy, society, language, science and technology will all look different. Most likely, you will not only NOT be able to compete with your contemporaries due to lack of skill and knowledge, you will NOT even be able to speak their language. You will need to take a language course first, before you can start learning useful skills. And that assumes some future benefactor is willing to pay to keep you running before you can start making money, survive independently in the future society.

To give an example, I am a software developer who takes pride in his craft. But a lot of the skills I have today will most likely be obsolete by the 31st century. Try to imagine what an 11th century stonemason would need to learn to be able to survive in today’s society.

1000 years into the future, you could be as helpless as a child. You could need somebody to adopt you, send you to school, and teach you how to live in the future. You—mentally an adult—could once again need a parent, a teacher.

(This is analogous to cryogenics or time-capsule sci-fi tropes. The further in the future you are unfrozen, the more irrelevant you become and the more help you will need to adapt.)

Patchy competence?

On the other hand, it would be a pity if a civilization which can emulate brain scans is unable to imbue them with relevant knowledge and skills, unable to update them.

For one second, let’s assume that they could. Let’s assume that they could inject your scan with 1000 years of knowledge, skills, language, ontology, history, culture and so on.

But then, would it still be you?

But then, why not just create a new AI from scratch, with the same knowledge and skills, and without the baggage of your personality, memories, and emotions?

Why think about this now?

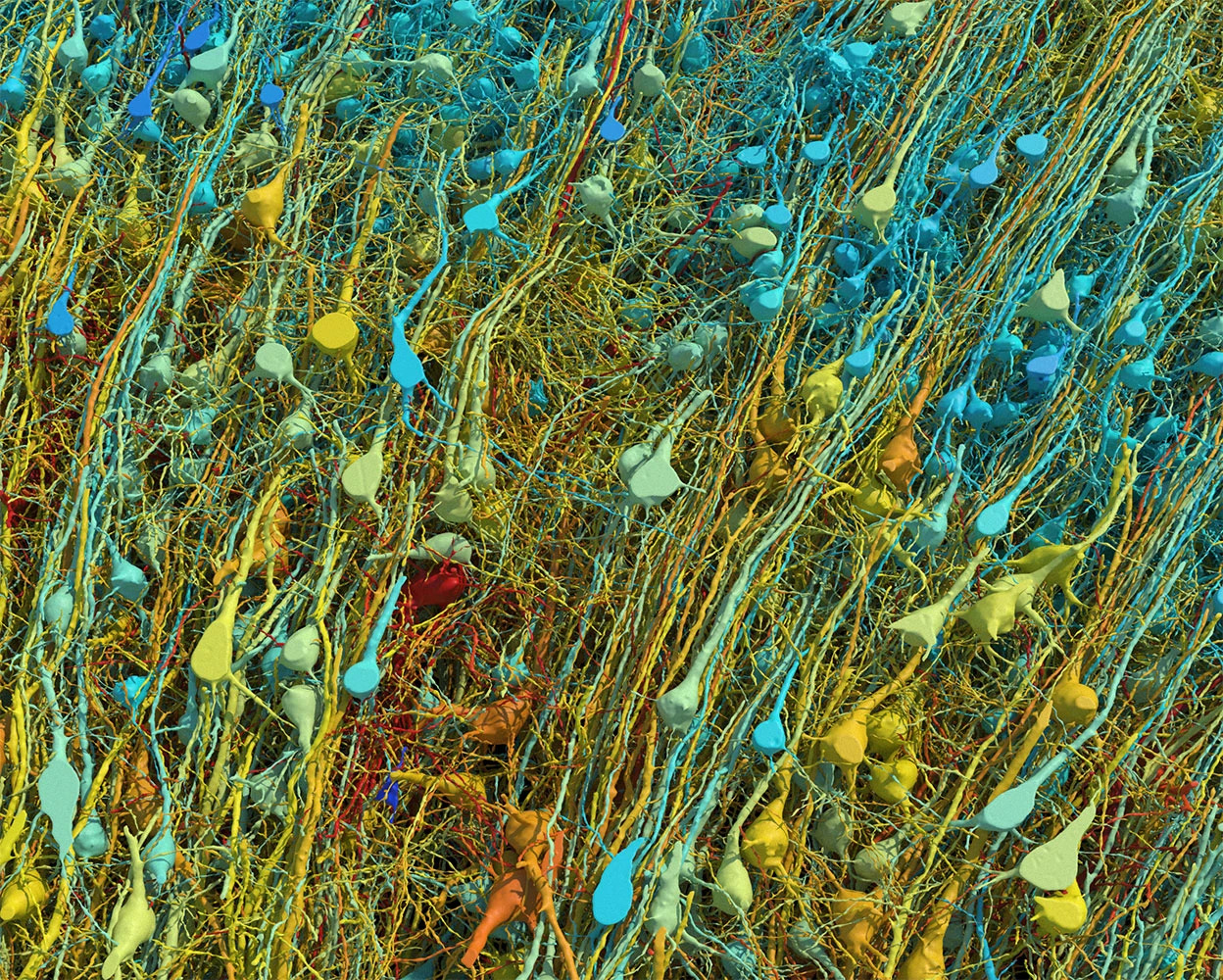

Google researchers recently published connectomics research (click here for the paper) mapping a 1 mm³ sample of temporal cortex in a petabyte-scale dataset. Whereas the scanning process seems to be highly tedious, it can yield a geometric model of the brain’s wiring at nanometer resolution that looks like this:

They have even released the data to the public. You can download it here.

An adult human brain takes up around 1.2 liters of volume. There are 1 million mm³ in a liter. If we could scale up the process from Google researchers 1 million times, we could scan a human brain at nanometer resolution, yielding more than 1 zettabyte (i.e., 1 billion terabytes) of data with the same rate.

That is an insane amount of data, and it seems infeasible to store that much data for a sufficient number of bright minds, so that this technology can make a difference. That being said, do we have any other choice but to hope that we will find a way to compress and store it efficiently?

Not only it is infeasible to store that much data with current technology, extracting a nanometer-scale connectome of a human brain may not be enough to capture a person’s mind in its entirety. By definition, some information is lost in the process. Fidelity will be among the most important problems in neuropreservation for a long time to come.

That being said, the most important problem in digital immortality may not be technical, but economical. It may not be about how to scan a brain, but about why to scan a brain and run it, despite the lack of any economic incentive.